Biomass (Technical Brief)

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Übersicht

- 2 Short Description

- 3 Introduction

- 4 Biomass use in the developing world

- 5 Technical

- 6 Combustion theory

- 7 Technologies

- 8 Charcoal production

- 9 Briquetting

- 10 Animal waste

- 11 Commercial utilisation of biomass

- 12 Other issues

- 13 Women, woodfuel, work and welfare

- 14 Resources

- 15 References and further reading

- 16 Useful addresses

- 17 Related articles

- 18 Deeplink:

Übersicht

Übersicht übernommener Howtopedia Artikel, Zum Übersetzten Artikel , zum originale Artikel

Short Description

- Idea: Energy through Biomass

- Information Type: Technical Brief

Introduction

What is biomass?

Biomass is the term used to describe all the organic matter, produced by photosynthesis that exists on the earth’s surface. The source of all energy in biomass is the sun, the biomass acting as a kind of chemical energy store. Biomass is constantly undergoing a complex series of physical and chemical transformations and being regenerated while giving off energy in the form of heat to the atmosphere. To make use of biomass for our own energy needs we can simply tap into this energy source, in its simplest form we know, this is a basic open fire used to provide heat for cooking, warming water or warming the air in our home. More sophisticated technologies exist for extracting this energy and converting it into useful heat or power in an efficient way.

The exploitation of energy from biomass has played a key role in the evolution of mankind. Until relatively recently it was the only form of energy which was usefully exploited by humans and is still the main source of energy for more than half the world’s population for domestic energy needs.

Traditionally the extraction of energy from biomass is split into 3 distinct categories:

Solid biomass - the use of trees, crop residues, animal and human waste (although not strictly a solid biomass source, it is often included in this category for the sake of convenience), household or industrial residues for direct combustion to provide heat. Often the solid biomass will undergo physical processing such as cutting, chipping, briquetting, etc. but retains its solid form.

Biogas - biogas is obtained by anaerobically (in an air free environment) digesting organic material to produce a combustible gas known as methane. Animal waste and municipal waste are two common feedstocks for anaerobic digestion.

Liquid Biofuels - are obtained by subjecting organic materials to one of various chemical or physical processes to produce a usable, combustible, liquid fuel. Biofuels such as vegetable oils or ethanol are often processed from industrial or commercial residues such as bagasse (sugarcane residue remaining after the sugar is extracted) or from energy crops grown specifically for this purpose. Biofuels are often used in place of petroleum derived liquid fuels.

In this fact sheet we will be looking at the use of solid biomass, and the associated technologies. For further information on the other biofuels see the fact sheet in this series entitled ‘Biogas and liquid biofuels’

Biomass use in the developing world

More than two million people in the developing world use biomass for the majority of their household energy needs. It is used mainly for cooking, heating water and domestic space heating. Table 1 below shows household energy consumption as a percentage of total biomass consumption in a number of selected countries in Africa. Biomass is also used widely for non-domestic applications.

|

Country |

Biomass energy consumption (% of total energy consumption) |

Household energy consumption (% of total biomass energy) |

|

Burundi |

94 |

78.5 |

|

Ethiopia |

86 |

97 |

|

Kenya |

70 |

93 |

|

Somalia |

87 |

92 |

|

Sudan |

84 |

90 |

|

Uganda |

95 |

78.6 |

Table 1: Household energy consumption as a percentage of total biomass consumption in a number of selected African countries

Source: FWD, 1992 cited in Karekezi, 1997

Biomass is available in varying quantities throughout the developing world - from densely forested areas in the temperate and tropical regions of the world, to sparsely vegetated arid regions where collecting wood fuel for household needs is a time consuming and arduous task.

In recent decades, with the threat of global deforestation, much focus has been given to the efficient use of biomass (as well as introducing alternative fuels) in areas where woodfuel is in particular shortage. Although domestic fuelwood users suffer greatly from the effects of deforestation, the main cause of deforestation is clearing of land for agricultural use and for commercial timber or fuel-wood use.

Many programmes have been established during the last 3 decades aimed at developing and disseminating improved stove technologies to reduce the burden, primarily borne by women, of fuelwood collection as well as reducing health risks associated with burning fuelwood. Technologies have also been introduced to help with the processing of biomass, either to improve efficiency or to allow for easy transportation.

Figure 1: Improved Cookstove in Kenya ©Neil Cooper/Practical Action

Crop and industrial biomass residues are now widely used in many countries to provide centralised, medium and large-scale production of process heat for electricity production or other commercial end uses. There are several examples in Indonesia of timber processing plants using wood waste-fired boilers to provide heat and electricity for their own needs, and occasionally for sale to other consumers.

Technical

Biomass resources

As mentioned earlier, natural biomass resources vary in type and content, depending on geographical location. For convenience sake, we can split the world’s biomass producing areas into three distinct geographical regions:

Temperate regions - produce wood, crop residues, such as straw and vegetable leaves, and human and animal wastes. In Europe short rotation coppicing (SRC) has become popular as a means for supplying woodfuel for energy production on a sustainable basis. Fast growing wood species, such as willow are cut every two to three years and the wood chipped to provide a boiler fuel. In the UK there is a functioning 12.6 Megawatt power plant which burns poultry litter (which has a relatively low moisture content) as fuel, and others which burn wheat straw. There are also many non-woody crops which can be grown for production of biofuels and biogas, and investigation of energy crops for direct combustion is underway. In western countries, where large quantities of municipal waste are generated, this is often processed to provide useful energy either from incineration or through recovery of methane gas from landfill sites.

Arid and semi-arid regions - produce very little excess vegetation for fuel. People living in these areas are often the most affected by desertification and often have difficulty finding sufficient woodfuel.

Humid Tropical regions - produce abundant wood supplies, crop residues, animal and human waste, commercial, industrial and agro- and food-processing residues. Rice husks, cotton husks and groundnut shells are all widely used to provide process heat for power generation, particularly. Sugarcane bagasse is processed to provide ethanol as well as being burned directly; and many plants, such as sunflower and oil-palm are processed to provide oil for combustion. Many of the world’s poorer countries are found in these regions and hence there is a high incidence of domestic biomass use. Tropical areas are currently the most seriously affected by deforestation, logging and land clearance for agriculture.

Combustion theory

For solid biomass to be converted into useful heat energy it has to undergo combustion. Although there are many different combustion technologies available, the principle of biomass combustion is essentially the same for each. There are three main stages to the combustion process:

Drying - all biomass contains moisture, and this moisture has to be driven off before combustion proper can take place. The heat for drying is supplied by radiation from flames and from the stored heat in the body of the stove or furnace.

Pyrolysis - the dry biomass is heated and when the temperature reaches between 200º and 350ºC the volatile gases are released. These gases mix with oxygen and burn producing a yellow flame. This process is self-sustaining as the heat from the burning gases is used to dry the fresh fuel and release further volatile gases. Oxygen has to be provided to sustain this part of the combustion process. When all the volatiles have been burnt off, charcoal remains.

Oxidation - at about 800ºC the charcoal oxidises or burns. Again oxygen is required, both at the fire bed for the oxidation of the carbon and, secondly, above the fire bed where it mixes with carbon monoxide to form carbon dioxide which is given off to the atmosphere.

It is worth bearing in mind that all the above stages can be occurring within a fire at the same time, although at low temperatures the first stage only will be underway and later, when all the volatiles have been burned off and no fresh fuel added, only the final stage will be taking place. Combustion efficiency varies depending on many factors; fuel, moisture content and calorific value of fuel, etc. The design of the stove or combustion system also affects overall thermal efficiency and table 2 below gives an indication of the efficiencies of some typical systems (including non-biomass systems for comparison).

|

Type of combustion technology |

Percentage efficiency |

|

Three-stone fire |

10 - 15 |

|

Improved wood-burning stove |

20 - 25 |

|

Charcoal stove with ceramic liner |

30 - 35 |

|

Sophisticated charcoal-burning stove |

up to 40 |

|

Kerosene pressure stove |

53 |

|

LPG gas stove |

57 |

|

Steam engine |

10 - 20 |

Table 2 efficiencies of some biomass energy conversion systems Source: Adapted from Kristoferson, 1991

Technologies

Improved stoves

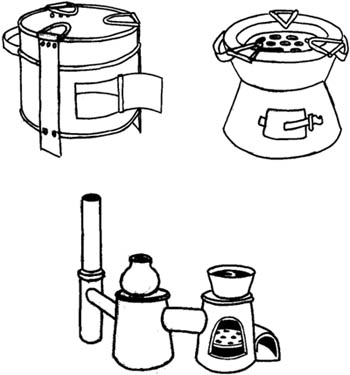

Much of the research and development work carried out on biomass technologies for rural areas of developing countries has been based on the improvement of traditional stoves. This was initially in response to the threat of deforestation but has also been focused on the needs of women to reduce fuel collection times and improve the kitchen environment by smoke removal. There have been many approaches to stove improvement, some carried out locally and others as part of wider programmes run by international organisations. Figure 2 below shows a variety of successful improved stove types, some small, portable stoves and others designed for permanent fixture in a household.

Some of the features of these improved stoves include:

• a chimney to remove smoke from the kitchen

• an enclosed fire to retain the heat

• careful design of pot holder to maximise the heat transfer from fire to pot

• baffles to create turbulence and hence improve heat transfer

• dampers to control and optimise the air flow

• a ceramic insert to minimise the rate of heat loss

• a grate to allow for a variety of fuel to be used and ash to be removed

• metal casing to give strength and durability

• multi pot systems to maximise heat use and allow several pots to be heated simultaneously

Improving a stove design is a complex procedure which needs a broad understanding of many issues. Involvement of users in the design process is essential to gain a thorough understanding of the user’s needs and requirements for the stove. The stove is not merely an appliance for heating food (as it has become in Western society), but is often acts as a social focus, a means of lighting and space heating. Tar from the fire can help to protect a thatched roof, and the smoke can keep out insects and other pests. Cooking habits need to be considered, as well as the lifestyle of the users. Light charcoal stoves used for cooking meat and vegetables are of little use to people who have staple diets such as Ugali, which require large pots and vigorous stirring. Fuel type can differ greatly; in some countries cow dung is used as a common fuel source, particularly where wood is scarce. Cost is also a major factor among low-income groups. Failing to identify these key socio-economic issues will ensure that a stove programme will fail. The function of an improved stove is not merely to save fuel.

Charcoal production

There are several methods for processing wood residues to make them cleaner and easier to use as well as easier to transport. Production of charcoal is the most common.

It is worth mentioning at this point that the conversion of woodfuel to charcoal does not increase the energy content of the fuel - in fact the energy content is decreased. Charcoal is often produced in rural areas and transported for use in urban areas.

The process can be described by considering the combustion process discussed above. The wood is heated in the absence of sufficient oxygen which means that full combustion does not occur. This allows pyrolysis to take place, driving off the volatile gases and leaving the carbon or charcoal remaining. The removal of the moisture means that the charcoal has a much higher specific energy content than wood. Other biomass residues such as millet stems or corncobs can also be converted to charcoal.

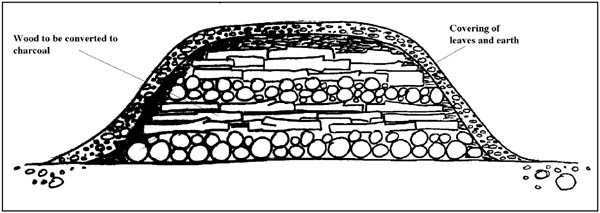

Charcoal is produced in a kiln or pit. A typical traditional earth kiln (see figure 3) will comprise the fuel to be carbonised, which is stacked in a pile and covered with a layer of leaves and earth. Once the combustion process is underway the kiln is sealed, and then only once process is complete and cooling has taken place can the charcoal be removed.

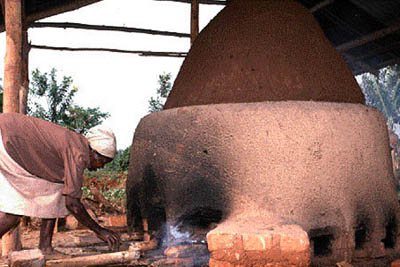

Figure 4: Charcoal Kiln, Kenya ©Heinz Muller/Practical Action

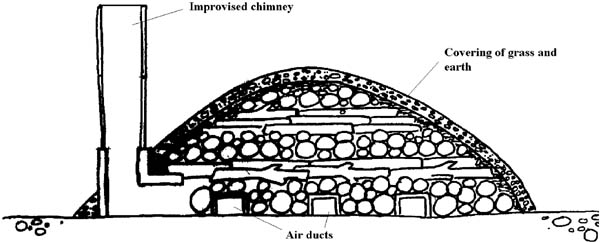

A simple improvement to the traditional kiln is also shown in Figure 5. A chimney and air ducts have been introduced which allow for a sophisticated gas and heat circulation system and with very little capital investment a significant increase in yield is achieved.

Figure 5: Improved Charcoal Kiln Found in Brazil, Sudan and Malawi

Briquetting

Briquetting is the densification of loose biomass material. Many waste products, such as wood residues and sawdust from the timber industry, municipal waste, bagasse from sugar cane processing, or charcoal dust are briquetted to increase compactness and transportability. Briquetting is often a large scale commercial activity and often the raw material will be carbonised during the process to produce a usable gas and also a more user friendly briquette. Some improved stoves have been designed specifically to be used with briquettes (Karekezi 1997).

Animal waste

Dung Collection

Many poor families in rural and urban areas collect dung as their source of income. There is a group of women in Bangladesh, who traditionally collect dung, make cakes and sell them to commercial markets. The traditional collectors of dung are teenage girls from poor families. They bring back dung to their homes and convert it into round cakes and cone-like sticks for drying in the open air

Dung is considered to be one of the best fuels for the traditional mud stove for the following reasons

Problems related to dung as a fuel are;

|

Source: Mohammed Aslam, Practical Action Bangladesh

Commercial utilisation of biomass

Biomass can be used for a variety of commercial activities. There are several technologies which employ direct combustion of unprocessed or semi-processed biomass to produce process heat for a variety of end-uses. The most common is the simple furnace and boiler system which raises steam for such applications such as tobacco curing, electricity generation and beer brewing. Biomass is also used for providing direct heat for brick burning, for lime burning and cement kilns. The advantage of using biomass is that it can be locally sourced, thereby avoiding shortages associated with poor fuel supply networks and fluctuating costs.

Other issues

Biomass energy and the environment

Concern for the environment was one of the major inspirations for early research and development work on improved stoves. One of the greatest paradoxes of this work is that, the more that is learnt about people, fuel and cooking, the more it is realised how little was understood about the environment and the implications concerning domestic energy use.

Initially, one environmental concern dominated the improved stoves work - saving trees. Today, this issue is considerably downplayed as time has brought a clearer understanding of the true causes of deforestation. At the same time, other environmental issues have become dominant - the household environment with its smoke, heat, lighting requirements, etc. have been given greater consideration. These micro environmental needs are often as complex as the broader environmental concerns and this is reflected in the fact that no one improved stove design can meet the needs of a wide and diverse range of peoples.

Large-scale combustion of biomass is only environmentally feasible if carried out on a sustainable basis. For obvious reasons continual large-scale exploitation of biomass resources without care for its replacement and regeneration will cause environmental damage and also jeopodize the fuel source itself.

Local manufacture of stoves

|

Since 1982, the Kenya Ceramic Jiko (KCJ), an improved charcoal-burning stove aimed at the urban market has been developed and manufactured by large numbers of small producers. The KCJ has two main components; metal and fired clay. Both these parts are made by entrepreneurs; the metal part (cladding) being made by small-scale enterprises or individual artisans, while the clay part (liner) is manufactured by slightly larger and more organised enterprises or women’s groups. The KCJ is sold by the artisans directly to their customers or through commercial outlets such as retail shops and supermarkets. The stove was initially promoted heavily to develop the market, by the NGO KENGO and by the Kenyan Ministry of Energy, through the mass media, market demonstrations and trade fairs. As a result of this substantial promotion, there are now more than 200 artisans and microenterprises manufacturing some 13,600 improved stoves every month. To date, it is estimated that there are some 700,000 such stoves in use in Kenyan households. This represents a penetration of 16.8% of all households in Kenya, and 56% of all urban households in the country. |

Source: Dominic Walubengo, Stove Images, 1995

Women, woodfuel, work and welfare

For resource-poor women the working day stretched from dawn to long after dark. The pressures on women’s time are heavy, cooking and fuel collection are among the most arduous of their tasks. The effects of inhaling biomass smoke during cooking are receiving attention from researchers; chronic bronchitis, heart disease, acute respiratory diseases and eye infections have been linked with smoky interiors, but the impacts of fuel shortage on cooking and nutrition are scarcely noticed.

As fuel shortages make extra demands on time and energy, women are driven to various coping strategies More time spent collecting fuel can mean less time growing or preparing food so that quality and quantity of food diminish. Malnourished women become more vulnerable to smoke pollution which damage their lungs, eyes, children and unborn babies. But improved stoves can cook faster and burn fuel more efficiently, which lowers levels of exposure to biomass smoke and releases time for other activities. Adapting kitchen design can also help remove smoke from the cooking area.

Greater technology choice can help to emancipate women from drudgery and give them more control over precious resources. In some places cooking is a particularly time-consuming task, so an improved stove which cooks faster may be a source of delight. Elsewhere, fuel management strategies by women save more fuel than carefully planned stove programmes. Stove technologists can offer choices, but decisions about household energy technologies should be left in the hands of women, the real experts on cooking.

Figure 6: Woman can design and Manufacture improved cook stoves. ©Simon Ekless/Practical Action

Resources

1. Karekezi, S. and Ranja, T., Renewable Energy Technologies in Africa, AFREPEN, 1997

2. Kristoferson L. A., and Bokalders V., Renewable Energy Technologies - their application in developing countries, IT Publications, 1991

3. Boiling Point, Issues No. 21,26,27,28,39, IT/GTZ.

4. Westhoff, B and Germann, D., Stove Images, Brades and Aspel Verlag GmbH, 1995

5. Stewart, B and others, Improved Wood, Waste and Charcoal Burning Stoves, IT Publications, 1987.

References and further reading

This Howtopedia entry was derived from the Practical Action Technical Brief Energy from the Wind.

To look at the original document follow this link: http://www.practicalaction.org/?id=technical_briefs_energy

Useful addresses

Practical Action

The Schumacher Centre for Technology & Development, Bourton on Dunsmore, RUGBY, CV23 9QZ, United Kingdom.

Tel.: +44 (0) 1926 634400, Fax: +44 (0) 1926 634401

e-mail: practicalaction@practicalaction.org.uk

web: www.practicalaction.org

Related articles

- How to Make a Cooking Box (Hay Box / Hay bag)

- How to Use Sun Power

- How to Build an Efficient Wood Oven

- How to Build a Winiarski Rocket Stove

- How to Build Solar Cookers

- How to Build the ARTI Compact Biogas Digestor

- How to Build the Vacvina Biogas Digestor

- Biomass (Technical Brief)

- Kerosene and Liquid Petroleum Gas (LPG)

- How to Build a Clean Dung-Burning Stove

Deeplink:

http://en.howtopedia.org/wiki/How_to_Build_an_Efficient_Wood_Oven